A Short History

The Royal South Australian Yacht Squadron (RSAYS) began its life as the South Australian Yacht Club (SAYC) on 5 November 1869. On 25 October 1890 Her Majesty Queen Victoria granted the title Royal South Australian Yacht Squadron, which it has borne ever since. The Admiralty warrant authorising wearing of the Blue Ensign was dated 4 November 1890.

The first race was held on 1 January 1870. The four competing yachts were the Curlew, Isabella, White Squall and Express. They ranged in waterline length from 13 to 19 feet.

Meetings of committees and the general body of Members were held in sundry hotels — the Clubhouse, Ship Inn and Largs Pier

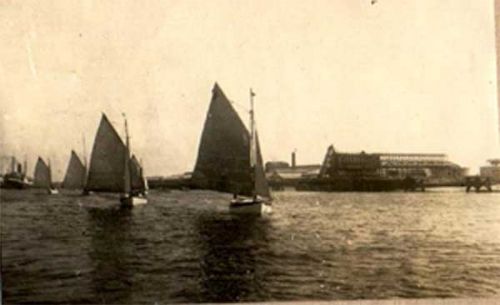

The crowded moorings at Birkenhead (WD Randall)

Beginnings

Birkenhead

In 1881 the Marine Board allocated to the South Australian Yacht Club a parcel of land and water on the Birkenhead side of the Port River, adjacent to where the Birkenhead Bridge was constructed many years later. Here the organisation prospered, although there was a lack of much in the way of social amenity.

In 1884 the Squadron purchased the freehold of the foreshore where the iron clubshed stood. Ramps and other works were undertaken over the next few years. The energetic and popular Honorary Secretary, Magnus Wald, instigated significant developments. In 1896 he produced a scheme to replace the indifferent structures at Birkenhead. As a result a roomy shed, containing lockers and other yachting conveniences, was provided. At least part of it survives at the time of writing this account.

One of the two RSAYS sheds at Birkenhead survived for more than a century. (JH Cowell)

The congested Port River circa 1890 (Australia Illustrated, 1892)

At a Monthly Meeting held on 10 January 1901, Members unanimously agreed to a merger of RSAYS and the Semaphore Club, of which Magnus Wald was the principal founder. Premises were purchased on the corner of Dunn Street and the Esplanade for £725, which were extended at an estimated cost of £1,750.

Amidst great controversy and after court actions, the Semaphore premises were sold in 1927. This occurred in part because erection of a large pavilion building obstructed a proper view of the waters off Semaphore and Largs Bay, where many races were held. Because of changes to the Licensing Act, the licensed premises were confined to a single venue, which was in an old bank in Port Adelaide. As was to occur in 1968, a few devoted Members treasured their familiar club, but the Squadron could no longer afford to maintain facilities for shrinking numbers of active participants in the social life of the club in that location

A typical Squadron race in the Port River in 1922, not long before the move to Outer Harbor. (Birnie album)

The Semaphore Club House 1901–1927

To revert to Birkenhead, the boatshed was extended by an additional 1,800 square feet, at a cost of £135. Members did much of the work in working bees, which have been a feature of Squadron developments ever since. One donated a new landing barge. The Squadron was thriving, having undertaken all this from its own resources, and by 1900 was free of debt.

The annual report for 1903 recorded the admission of 25 new members during the year, and vessels on the register now numbered 54. The mooring berth was deepened and enlarged by the Marine Board. A newspaper reported, “Their financial position has improved beyond their most sanguine expectations.”

Improvements that year (costing nearly £100) included strengthening the landing stage, installation of a telephone, building a spar shed and extra lockers etc at Birkenhead, plus decorating the billiard room at the relatively new Semaphore social clubhouse. The balance of assets over liabilities was now £2,046, an increase of £376.

The Marine Board granted definite tenure and extended the mooring berth in the Port River at a rent of £20 per annum for 10 years.

In 1905 the ramp was found to be rotten, due to Teredo navalis. It was replaced with a solid one of stone and cement.

The hull of AG Rymill’s Avocet emerges from Ben Weir’s shed beside the two Squadron sheds, 1909. (Rymill Gifts)A typical Squadron race in the Port River in 1922, not long before the move to Outer Harbor. (Birnie album)

Quei drifts past the pontoon at Birkenhead (Birnie album)

With the introduction of six o’clock closing in 1916, the licence of the Semaphore Clubhouse was transferred to new premises at Port Adelaide, where the Squadron bought the Bank of Australasia building. Here many of the social activities were concentrated, leaving the Semaphore premises for use mainly on days when sailing races were conducted from the jetty there. Members who lived nearby also made use of them.

Quitting Birkenhead

As early as 1912 the Marine Board declared its intention to order the removal of yachts to Outer Harbor. An undated newspaper cutting is headed, ‘Removal of Yacht Moorings’ —

The yacht moorings of the Royal South Australian Yacht Squadron are to be removed from their present site at the west end of Birkenhead to the foreshore near the Outer Harbor. This is the dictum of the President of the Marine Board, who stated at a meeting of the Board on Thursday that the contemplated alteration had the sanction of the members of the Squadron. The space now occupied by yachts is needed for vessels of the mercantile service, and Mr Searcy thinks yachtsmen will appreciate the change. At the new site which has been selected there is more room, and it will be advantageous on the score of cleanliness. The North Arm, said the President, would have been a splendid site, but it was too isolated, whereas the moorings near the Outer Harbor would be easily accessible by train. The change is not likely to take place for some time. It was only reported to the Board, remarked the President, because it was in the air.

In April 1917 the Birkenhead premises were compulsorily resumed by the Marine Board ‘for public use’, but for the time being there was no change. In 1920 a newspaper reported,

The committee [of the Squadron] were pleased to be able to report that a satisfactory arrangement had been made with the Marine Board for the deepening of that section between the Squadron’s shed and Jenkins’s Slip for the accommodation of yachts on the registers of the Squadron and the Port Adelaide Sailing Club. When these deepening operations were completed, the Board would grant to each club a lease of one moiety of the area.

In 1921 a septic tank was installed at Birkenhead at a cost of £63 and a tender was made for lease of Slip Number Four (Pickhaver) for seven years at £52 per annum (pa). A stove was bought for the “cottage” at Birkenhead. The Secretary of the SA Harbors Board made an offer of £2,550 compensation for resumption of property, which was accepted. A lease on the Birkenhead property was offered at a rental of £100 pa for 21 years, plus rates and taxes.

A “lean-to” was erected to protect motor cars and a balcony was planned, together with new lockers and some extension of the shed at a cost of £2,620. Originally this was to be financed by issuing debentures to Members, but in August 1922 it was decided to do so through an overdraft and by quitting the premises in the old Bank of Australasia building at Port Adelaide.

In June 1922 the Harbors Board offered to extend the lease at the McEndrick Street end of the property by 60 feet at an annual rental of £35 for 21 years. New moorings were laid in an extension of the previous water lease.

The Squadron seemed secure.

By 1923, however, it was clear the Squadron must move to Outer Harbor, and the Birkenhead premises were vacated by 31 July that year, six months ahead of the deadline. The background to this abrupt reversal has not been obtained. The government of Sir Henry Barwell survived until April 1924, so there seems not to have been a direct political reason. I suspect that Commodore AG Rymill, a forceful individual in his first year in office, may have urged his fellow power brokers in the Squadron to seize the opportunity at Outer Harbor before somebody else did. If so, no documentary confirmation has yet been found.

A newspaper report of the new “boat harbour” read,

This is situated at the northern end of the [Outer] Harbour, and close inshore. It is well protected from all weather conditions, and should prove an ideal place for the club’s new quarters. It is proposed in the near future to build a shed on the shore opposite the mooring space, with lockers, petrol store, motor shelter and other facilities. A lease has been secured from the Harbors Board on reasonable terms, and the committee feel that removal from Port Adelaide is a step in the right direction.

A claim for compensation totalling £3,175 for the confiscated property was submitted to the Minister of Marine. The overdraft with the National Bank was increased to provide funds for financing what was described as the Outer Harbor scheme.

Outer Harbor

A Harbors Board offer was accepted to dredge an area 400 ft by 300 ft, with space on the shore of 150 ft by 150 ft at a total annual rental of £150. An extra 30 ft was subsequently offered for an additional £25 pa.

The basic iron shed, the core of which has survived to the time of writing, was constructed by EH McMichael, but no record has been found of what it cost. A loose piece of paper in a draft of the 1969 centenary history implies that the Harbors Board may have paid for it, but the documents in State Records have not yet been consulted.

‘The Basin’ at Outer Harbor, Christmas 1922 (Birnie album)

A caretaker was appointed at a salary of £4 per week, plus free use of a new small weatherboard cottage and the opportunity to earn small sums doing work for Members.

(In 1919 the State Living Wage was £3.19.6, which rose in 1926 to £4.5.6. Reflecting the impact of the Great Depression it fell in 1931 to £3.3.0 and did not again exceed £4 until the wartime inflation and labour shortages of 1940.)

Mooring fees were initially set at £1 pa for vessels up to 20 ft, with an additional £1 pa for each additional 10 ft or part thereof. Lockers would be 10/- pa; dinghy space 10/- pa; and magazine space [?] 5/- pa. Benzine would be stored in drums for purchase by Members. Commodore AG Rymill bought from the sale of the Grand Central Hotel some furniture which has survived in the Squadron to the present day. It is not clear whether this was by donation or use of Squadron funds.

The new premises were officially opened by Commodore AG Rymill on 24 November 1924, that being the day of the Opening Demonstration for the season.

The Squadron was heavily dependent on Members for establishing itself at Outer Harbor.

The first yachts arrive at the new Outer Harbor premises (Birnie album)

Avocet at the original pontoon, 1924 (Rymill Gifts)

On 16 November 1994 Mr Denis Winterbottom, who was then 84 years of age, recalled helping his father in the working bee to construct the first rough track from the vicinity of the Outer Harbor Railway Station to the south-west corner of the new premises. This was some time in the summer of 1924–25, when he was a schoolboy at Saint Peter’s College. He also recalled horses and scoops excavating sand at the Squadron.

Three tons of loam and 1½ hundredweight of sulphate of ammonia were purchased to establish a lawn, with the work done by Members. Presumably the caretaker was left to push the new lawnmower, which would not have had an engine. In the same way the Squadron bought the pipes and fittings to connect water and connected electric light. In a foretaste of marina living, Commodore AG Rymill extended electricity to his yacht Avocet.

At this time motor boats outnumbered sailing craft, with much interest in the racing craft called hydroplanes. Special facilities were installed for them.

The new wharf just inshore from the floating pontoon for the handling of small hydroplanes has just been completed. This is directly in front of the new wing to the shed, which will be retained solely for hydros, and the main shed floor reserved solely for sailing and ordinary dinghies. (25 February 1926)

Spectators crowded on to anchored vessels to watch the Griffith Cup of 1923, won by AG & ES Rymill in Tortoise II.

An estimated 30,000 people jammed every vantage point to watch the Rymills’ somewhat anticlimactic victory. Commodore Rymill arranged that those on the wharf paid 2/- each for entry. That would have been a welcome boost to Squadron funds.

The first slip at Outer Harbor was established in October 1925. It was a simple device, able to take no more than two yachts at a time. Fees were set for vessels under 20 ft at 5/- per day; for those under 30 ft at 10/- per day; and for those over 30 ft at 15/- per day.

A new caretaker, Mr AO Shaw, was appointed at a salary of £4.5.0 per week “with cottage and lighting”. He would have been relieved when a fence was constructed round it. In March 1926 he was granted a bonus of twelve guineas (£12.12.0) “in recognition of the splendid manner in which he has carried out his duties during the last six months”.

Unspecified improvements at Outer Harbor were undertaken in late 1925 at a cost of £476.12.2. In 1926 the hydroplane wharf was constructed, to which the Rymill brothers and other Members with racing motor boats contributed significantly. The structure survived until the southern foreshore development of the 1980s.

The Hydroplane Wharf, about 1926 (Darian Smith)

To save the cost of slipping, many owners careened their boats for maintenance. This was Mannara, built by Searles of Birkenhead for Mr CF Haselgrove in 1924. (Don Haselgrove)

The Port Adelaide premises in the old bank were offered for sale at £5,500 and by a narrow majority the General Committee decided to dispose of those at Semaphore. This was a polarising issue, which eventually led to significant loss of Members to a reconstituted Semaphore Club. It didn’t survive after the Second World War.

The Vacuum Oil Company installed a bowser and pump in order to supply petrol to Members. First grade benzine cost 2/3 per gallon and second grade 2/1. Antifouling paint was sold by the Squadron to Members at £1.10.0 a gallon (red), 15/6 for ½ gallon (red) and 17/6 for ½ gallon (green). The pontoon sank and had to be replaced.

In 1928 the dredged area was extended. The original basin involved removal of 50,000 cubic yards of spoil, at a cost (in 1923) of ninepence to a shilling per cubic yard. Depth ranged from 4 ft 7 in to 8 ft 2 in. Unfortunately, the cost of this was not recorded, but it was born entirely by the Squadron.

Outer Harbor was established to provide sheltered wharfage for shipping in 1908. It was a dreary place. The only dwellings were two or three cottages for the families of the men employed in pilotage and the like. A new arrival to South Australia confronted bleak iron sheds on the wharves with an adjacent railway station. There was no shop or other protection from the elements. A narrow sealed road passed through deserted sandhills to the village of Largs and places beyond. It was often partially covered by drifting sand. The avenue of Norfolk Island pines was planted in 1936 for the State Centenary.

East of the Squadron premises was a tidal creek, and to the north were mud flats at low water and an expanse of sea to Torrens Island and Saint Kilda when the tide rose. Access to the north and east was possible only at low water. Mosquitoes were a menace.

There was nothing to attract a visitor other than the inducement of sailing, fishing or the transient excitement of racing by either motor boats or yachts. One significant advantage was readier access to the open waters of Saint Vincent Gulf rather than negotiating the loop of the Port River with its shifting sandbanks and quite heavy commercial traffic.

Protection for moored vessels was inadequate. The sand Section Bank on the right bank of the Port River went under at high water in strong north-west gales. (It was raised with rocks many years later, when the container berth was established.)

Regularly moored craft broke free and damaged each other. On at least one occasion a substantial motor boat was stove in and sunk. In an initial attempt to improve this, the Squadron deposited some old barges across its north-western and northern perimeters, but they eventually broke up and became useless for their intended purpose.

At low water on a calm day in about 1927–8, there was a misleading sense of protection from the combination of old barges and the undredged north bank. The yachts were moored N–S, until damage caused by gales resulted in relocation to E–W, to match those in the front row. (Birnie album)

Amenities were minimal. Upstairs were a couple of toilets and showers each for gentlemen and ladies. An area behind a partition with some clothes hooks was designated ‘For Senior Members Only’. Other than a solitary power point with an electric kettle, there were no catering facilities. Members had to bring their own, and the Squadron hired things for big occasions such as Opening Day.

There was a single slip beside the residence of the caretaker, and a shed erected by Professor Mark Mitchell for his vessels. This was destroyed by a storm in 1938. At the southern edge of the property were roofed enclosures to protect motor cars from rain and blowing sand.

The social life of the Squadron was divided. Locals used the Port Adelaide and Semaphore Clubhouses until they were sold. From 1935 to 1968 Members (who must be British gentlemen) with access to Adelaide used the licensed premises in a basement in Grenfell Street, mainly as a place for city businessmen for lunches. Women were admitted on one night a year. As a result, there were many social Members who had limited if any interest in what went on at Outer Harbor, other than special events once or twice a year. Developments there depended on boat owners, whose prime commitment was necessarily to their own craft. At least one Secretary rarely went there.

The tin shed in the swamp stagnated until after the Second World War.

Ardale (briefly one of the Wylos) on the RSAYS slip, 1927 (Birnie album)

Avocet and Grelka moored in front of Mitchell’s shed, showing the original eastern boundary fence, with the Hydroplane Wharf in the foreground.

Temporary Removal

After the fall of Singapore in February 1942, there was genuine fear throughout Australia of Japanese invasion. Although the threat in South Australian waters was minimal, precautions were taken.

Barbed wire barricades were erected on metropolitan beaches. The Birkenhead and Jervois bridges were drilled for demolition charges. Place names were removed from post offices, but few other buildings, public or private. Machine gun emplacements were constructed to defend such targets as the Glenelg tramline at Morphettville and the Sturt Creek amid the market gardens of Warradale. In Adelaide important buildings like the General Post Office were sandbagged. Trenches were dug everywhere for shelter, and large concrete pipes were placed along North Terrace for this purpose. The Governor of the day was photographed in one to inspire the citizens with confidence. Men returning from combat remarked that anybody in them would most likely be killed by blast. Each night searchlights roamed the skies over Adelaide, although the only anti-aircraft guns in South Australia protected the new shipyards at Whyalla — where for many months there were no search lights!

No 2 Division RAN NAP, July 1943 (HW Rymill album)

The Royal Australian Navy compulsorily acquired some Squadron vessels, which served as far afield as the Philippines. Others, together with Members, were employed locally in the work of the Naval Auxiliary Patrol. The remaining vessels in the fleet were relocated from the pool at Outer Harbor to Number Three Dock at Port Adelaide. Fuel rationing compounded shortage of crew in suspending most Squadron activities at this time, both formal races and informal cruising. Vessels entering and leaving the Port River were required to report to the Pilot Tower coming and going. It was said that one neglecting to do so received a bullet hole through the mainsail from an unduly conscientious sentry.

The premises at Outer Harbor retained their storage functions for the small number of vessels operating the NAP. Sea Scouts had some training there, in pretty spartan conditions.

At the end of the War in 1945, it was apparent that the pool had silted up considerably since it was originally dredged in 1923 and extended in 1928. The yachts were located in the North Arm while the Squadron undertook to have it deepened and enlarged.

Return to Outer Harbor

Seacraft March 1950: 191. Under South Australian Notes:

In 1954 the only significant change since 1926 was construction of the western dinghy shed and a second walkway to the pontoon. The eastern shed was originally built for hydroplanes. (HW Rymill album)

New Mooring Pool Opened

Most colourful yachting event of the season, so far, was the opening of Royal South Australian Yacht Squadron’s new mooring basin at Outer Harbor on January 21. Nearly 100 power and sailing craft took part in the demonstration which accompanied the ceremony.

Lady Norrie, who with His Excellency the Governor (Sir Willoughby Norrie) was aboard the flagship Sir Wallace Bruce, cut the ribbon across the entrance to the pool. State Government and Harbors Board representatives were among the official party.

Commodore HJ Kemp declared the pool open from in front of the flag bedecked clubhouse and later took the salute aboard the flagship during the sail past. Rear Commodore HW Rymill led power boats in Sea Hawk and Vice-Commodore CP Haselgrove, aboard Neptune Island race-winner Nerida, was in charge of sailing craft.

The basin was enlarged during the winter to accommodate about 130 boats — twice as many as last season.

In the early postwar years notable changes took place in the activities undertaken by Members. The speedboats known as hydroplanes were advancing to extinction (so far as the Squadron was concerned) and sailing craft supplanted motor boats as the dominant group. Racing expanded considerably, both inshore on summer weekends and in an increasing number of long distance offshore races. Larger vessels arrived, so that slipping facilities were increasingly inadequate.

Equally importantly, in Squadron politics the pressure steadily mounted to concentrate on the actual pastime of yachting rather than to have much of the activities (and resources) dominated by Members who used the City Clubrooms as a business men’s luncheon club.

Expansion at Outer Harbor

In contemplating enhancing facilities at Outer Harbor the Squadron faced formidable problems. The most important constraint was the matter of the lease. This was on a monthly basis, with no certainty that if it were to be terminated compensation would be paid for improvements. Without a secure lease, the Squadron could not borrow from a financial institution, and capital works must be financed entirely from the resources of current Members.

One great advantage was that the Squadron enjoyed a virtual monopoly of secure moorings under the eye of a resident caretaker to serve the whole of metropolitan Adelaide. The Port Adelaide Sailing Club had the disadvantage of congested water and premises ashore. Security was a problem. The Birkenhead Bridge (completed in 1940) must be opened every time yachts went to and fro. There were public moorings available in the Port River and west of the Squadron lease at Outer Harbor, but boat owners faced perpetual problems of theft and vandalism. The Small Boat Club and the Cruising Yacht Club of South Australia did not exist. The small pool at Glenelg entered through the Patawalonga lock was constructed in 1960. It accommodated no more than a handful of shoal-draft craft. There was no public access to Torrens Island, where the power station was yet to be built. The outcome was great pressure on the moorings in the Squadron pool, with at times significant waiting lists.

Resources at Outer Harbor must be expanded and enhanced. The problems were how to do it and how to pay for it. The only means were funds and effort provided by Members. There was no contribution from government sources. It was at that time not possible to borrow from a financial institution such as a bank, when at a month’s notice the premises could be closed, forcing the yachts to go elsewhere, with nothing comparable available near Adelaide.

Fortunately there was an imaginative Commodore (Dr Geoffrey Verco) with a determined General Committee and a core of strongly supportive Members. In the winter of 1959 severe storms caused a lot of damage to installations at Outer Harbor, together with erosion of the waterfront. Urgent action was required.

Congenial relations with the Harbors Board allowed the Squadron to acquire a considerable area to the east and north and — most important of all — an extended lease for twenty years. In a series of memorable working bees the perimeter fences were progressively extended to the east and north. Using a borrowed sand pump the pool was deepened and the spoil was used to good effect to build a bank to hold at bay the potential swamp in the north-east corner. A stone retaining wall was built on the eastern bank and progressively extended along the south bank.

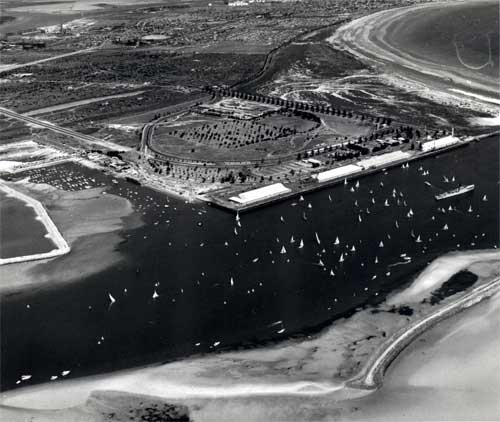

By 1961 the pool was completely saturated, with a waiting list for moorings. Those in the front row regularly went aground at low water. The Eastern Dinghy shed and its pontoon eased congestion for lockers and dinghies in the Clubhouse. Two of the old barge hulls can be seen. The eastern stone-walling and relocation of the boundary fence came a few years later. The roof of the old car shelters can be seen at the southern boundary behind the Clubhouse. Entrance was at the SW corner. West of the pool (out of the picture) nondescript small craft lay on public moorings. Some were waiting for a vacancy to enter the pool

During 1961–62 a virtually compulsory loan scheme was established. Both boat-owners and other Members provided interest-free loans over a five-year period, to be repayable in the distant future. Most were subsequently forgiven.

With these funds, major development began. Dredging was professionally undertaken to accommodate an increasing number of larger vessels. A new and much larger slip was installed, followed by a second slip. A traverse system allowed yachts to be hauled out for extended periods.

To overcome peak pressures the traverse area was greatly expanded and sealed with concrete. This was excessively ambitious, and it has never been fully utilised.

At this stage the decrepit old Clubhouse remained virtually unchanged from how it was forty years previously. There were still no facilities beyond the electric kettle and a few tables and chairs. At least the lawn area was extended and tree planting enhanced the barrenness of the past.

In 1964 a “comfort station” was established upstairs in the Outer Harbor Clubhouse. Here alcohol was unlawfully made available, although there was a fright when some prominent citizens were convicted of a similar activity at a golf course. This had the good effect of accelerating long overdue amendments to the Licensing Act. For the first time some social amenities began to appear at Outer Harbor for those who used the premises and otherwise had only what they had on the yachts or brought with them.

Ablution and toilet facilities bordered on the squalid. Over the next year or so toilets and showers were removed from upstairs and a new block was constructed, which remains in use. The new facilities for women were at first quite inadequate for big events (and still are) but at least they were improved.

A significant advance was construction of an office in the eastern extension of the Clubhouse for the Secretary-Manager, who for the first time regularly came to Outer Harbor at weekends. One of his predecessors was seen there no more than a couple of times a year.

A Junior Clubroom was established near the caretaker’s cottage, only to be relocated and used for other purposes when additional storage area was required. Two sheds were erected near the southern boundary for shipwrights and a third for the Squadron’s own purposes.

The final acquisition of land to the east, coupled with renewed dredging, allowed the Squadron to level and plant an area of lawn near the eastern dinghy shed, where extra toilets were installed. The traverse area was paved and power installations were brought up to commercial standards. A generous member donated security lighting. A better perimeter fence was erected to enhance security.

Commodore Alan Smith closely involved himself in these important developments, and continued to devote his time and energy to successive projects until shortly before his death in 1998.

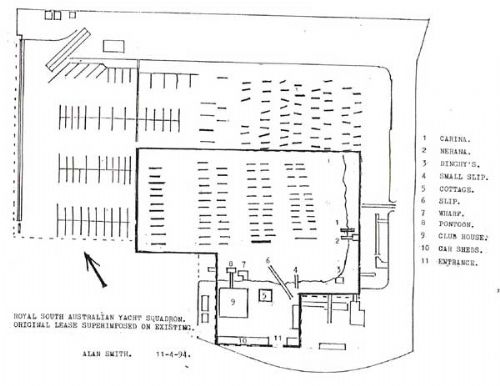

Alan Smith’s diagram recorded all the salient changes from 1923 to 1994.

Consolidation and Development at Outer Harbor

Under Commodore Alan Smith, in 1968 the polarising decision was taken to close the city clubrooms and concentrate all activities at Outer Harbor, including transfer of the liquor licence. What had been the ladies toilets and showers upstairs became the nucleus of a kitchen and bar. The old partitions were swept away to create an open dining room area. The Tom Hardy Library from Grenfell Street was relocated on the western side of the building, which has posed problems resulting from heat and light on some of the old books and colour photographs. A handsome trophy cabinet was obtained. Burgees from yacht clubs in other states and countries were framed and placed around the room.

A new entrance foyer and an internal staircase were constructed.

The result was creation of a fine area, to which Members can bring guests with pleasure and pride.

What could be called the infrastructure has required repeated refurbishment and replacement, which has been costly, without there necessarily being much to show for it.

By the Centenary Regatta of 1969–70 work had begun on reclaiming the area north of the Squadron, which became the Container Wharf and its related services. Small vessels can be seen on the public moorings west of the premises. In this view, taken at low water, the potential area available from dredging can be readily seen. The western boundary of the lease was extended to its definitive location in 1989.

As long ago as about 1966 and led by some generous and gregarious Members, an enclosed area was built on the ground floor on the western side, to be used for evening barbecues. This was called Walker’s Wurley after Jock Walker, a generous and popular Member. Subsequently it was adapted to comprise a regatta office and is a venue for small meetings. Nearby, in 1994 a “gazebo” barbecue was constructed. Excellent shaded barbecues were established north and east of the traverse area and the eastern dinghy shed.

The caretaker’s cottage was demolished and a demountable building for this purpose was placed at the western boundary. This allowed a sail drying rack to be placed between the Clubhouse and the traverse area, which was later relocated east of the slips. A temporary Juniors’ clubroom was located south of this, to be relocated at the south-east corner of the premises and used for other purposes when Junior activities temporarily lapsed in about 1975.

In 1992 a staging known as the Quarterdeck was erected to complement the extension of floating pontoons along the whole of the south bank, apart from the gaps required for the two slips.

Enthusiastic Members established a new (and much better) Junior Clubroom, on the southern side of the property near the western boundary and then relocated it to the north bank.

Ever since 1924 the open space on the ground floor of the Clubhouse was used to store dinghies and for large lockers for boat owners. Similar lockers were placed in both the western and eastern dinghy sheds. This area had to be cleared and reinstalled by working bees every Opening Day. Envious eyes regarded the space as having other potential uses, and some was taken on the northern side to construct Jimmy’s Bar. This complements the Quarterdeck and is a popular venue for informal and convivial gatherings, especially after races.

From the early days at Outer Harbor yachts were moored fore and aft in parallel rows facing north-south. In response to the major threat, a storm from the north-west, they were soon changed to lie east-west. They are loosely called trots moorings, although not strictly in conformity with the classical situation at Cowes, home of the Royal Yacht Squadron. Moorings were maintained by Members, sometimes quite inadequately. Access was by dinghy or (over the last twenty years) by Squadron tender at weekends. Vessels were brought to the solitary pontoon or the adjacent hydroplane wharf to load stores, obtain fuel and water and (in defiance of by-laws) as an informal marina.

As the Squadron and its fleet expanded, pontoon facilities must be extended, which was achieved along the southern bank. With increasing demand for marina facilities, these were installed in two stages and in 2001 with a third agreed in principle.

The Quarterdeck, 1999

They are entered from the north bank, where an ablution block was built, incorporating services for the government departments which lease facilities, including mooring space, from the Squadron. Car parking required paving nearby, which expanded the area potentially available for dry-standing of yachts hauled out when not in the water. This development has had the undesirable effect that many people drive to and fro without entering the Clubhouse on the south bank. The Squadron’s social life and income have suffered accordingly.

In about 1968 the character of the Squadron was forever drastically altered. The Harbors Board began a program of land reclamation extending from immediately north of the Squadron pool. For several years we endured caustic dust blowing over vessels and people whenever there was a strong north wind, until at last the project was completed.

Immediately to the north of the Squadron pool Port Adelaide’s container berth was established, with three traverse container cranes operated on a 24-hour basis according to need. A sealed road against the eastern boundary brought traffic closer than it had ever been. Adjacent to it is a spur standard gauge railway line. Nearby on the western side of the premises vast car parks have been established for import and export of motor vehicles.

The tranquil peace of the past has been permanently lost.

By 1991 the Squadron’s fixed and floating breakwater provided excellent shelter from NW gales. At the NW corner are sheds for government use, the Junior Clubroom and a launching ramp, together with an amenities block. The marina was fully occupied. A new entrance had not yet been constructed at the southern boundary. The Trailer Boat Club and Sea Scout training building remained immediately west of our Clubhouse. Government tenders and pilot craft lay for many years to piles on the south bank of the entrance channel, but they have been relocated into pens near our north bank, adjacent to the loading ramp.

Meanwhile the local area changed equally dramatically, although more aesthetically. A new boat harbour was constructed at North Haven, which accommodates on freehold land and water of the Cruising Yacht Club of South Australia, together with public moorings and commercial maintenance facilities. Extensive land division and housing development have replaced the original sandhills. Lady Gowrie Drive and other roads have been considerably upgraded to take heavy traffic.

Summary

- Royal South Australian Yacht Squadron started its life in 1869 and moved its vessels with ancillary resources (slip etc) from Birkenhead to Outer Harbor in 1924.

- From 1869 until 1968 the social life of the Squadron mostly concentrated elsewhere, but since then all activities have been exclusively at Outer Harbor.

- In 1923–24 an iron shed was constructed to provide shelter for dinghies and lockers, together with minimal toilet and changing facilities, but no social amenities.

- The original pool was dredged by the then Harbors Board, but since then all dredging and other developments for yachts (including marinas) have been undertaken exclusively by the Squadron from its own resources, involving a huge volunteer input.

- The ‘Tin Shed in a Swamp’ remains the basis of a pleasing and functional Clubhouse. This has problems, however, with infrastructure, meeting fire regulations and its ability to provide all that is required, including adequate office space. Extensive redevelopment or replacement is fully justified, but cannot be afforded at present.

- The Squadron has developed the general premises to the best of its ability, with a fine entrance from Oliver Rogers Road, attractive landscaping and appropriate paving, both for hard-standing yachts and for car parking.

- Marinas are progressively being developed to accommodate increasing numbers of vessels. New buildings on the north bank provide showers, toilets and facilities for government departments. Junior activities have been concentrated there. A large slip is provided for vessels on trailers.

- The Squadron is an old organisation which has undergone corporate rejuvenation in the last few years. It is strong and secure, continuing to provide a unique and notable component of yachting in South Australia.

- This was sealed in 2001 with purchase of the premises from Portscorp, the successor to the old Harbors Board.

- Our future is assured.